600km is far. That’s like cycling from Glasgow to the outskirts of London. Or Glasgow to the Falkirk Wheel 32 times. Or the length of Byres Road 600 times.

There’s no escaping the sheer distance, no matter the mental gymnastics you employ to make it feel like less when confronted with it.

And that’s exactly what I was confronted with last month as I lay on the floor of North Kessock Village Hall at 1am in my sleeping bag crammed alongside 30 or 40 other riders, counting down the hours till my alarm was set to go off at 5am, wondering what led me to this point.

Part I: Cycling History

“For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move.”

- Robert Louis Stevenson

I’ll spare you the boring biography but I’ve never considered myself a cyclist in the sense that I recreationally go out on my bike for it’s own sake. I’ve never watched the Tour de France and until recently I couldn’t tell you what a rear cassette was.

But what I have always enjoyed is wondering about the horizon, what’s over it, and if I could get there.

A bike is the perfect medium for this. You get yourself there under your own steam and you get to notice the landscape change in a way you miss if you’re in a car, train or plane.

There’s a sense of having travelled, and in reaching your destination, a sense of having truly got there. You didn’t sit down, put on a seatbelt and teleport. You’ve seen what connects your destination to where you started. You acquire a deeper understanding of the country and the landscape.

Through the lens of cycling, the world grows immensely. What was previously a short drive is now an afternoon’s riding away. A short ride from home can expose you to a million curiosities in areas and towns you only vaguely knew of. Cycling further afield, beyond the familiar has a sense of exploration and discovery that can’t be matched as readily and easily for most people.

My first experience of this was at 13 or 14 convincing my friends in high school to cycle to Edinburgh from Falkirk, where I grew up.

You need to get a train to Edinburgh, that’s crazy. No way can you cycle that. But we’d seen the signs on the canal saying EDINBURGH 31 MILES. Maybe it was doable.

And so with school bags filled with 30 pence Asda chocolate and tuna sandwiches, we set off and sure enough made it to Edinburgh after what felt like an epic voyage. We’d gone further than anyone I knew. It gave us a feeling of independence and a sense of confidence that can be so valuable as a young teenager. I loved it.

That isn’t to say I had an epiphany at this point and took up the mantle of cycling. Other passions and hobbies took precedence and except for one or two bike packing trips, cycling took a backseat.

It wasn’t until the Covid lockdowns that cycling came to the fore. I was time rich and cash poor. Cycling was the perfect thing to do.

10 mile rides turned into 30, which turned into 50, then 70 and so on.

There were a few of us doing this together, collectively pushing our limits. We were on borrowed mountain bikes, wearing trainers and backpacks. Military surplus ponchos if it rained.

The culmination was a multi-day bike packing trip to Stornaway from Glasgow averaging 60 miles a day. On some of the ferries we would see other bike packers with their lycra, frame bags and noticeable lack of loose banana peels and mess tins tied with bungees to the side of their pannier racks.

Although this adventure was to end in disaster with me eating an old ration pack dated from 1998 and the subsequent food poisoning leading to its contents covering a percentage of the Isle of Uist in the double digits, it nonetheless boosted our confidence that we could cycle far and consistently.

It started as a bit of a joke, but we wondered if it was possible to cycle from Glasgow to Inverness in one go. The furthest we’d gone up to that point was 100 miles. Inverness was 200.

We weren’t completely destroyed after 100 miles, if we could just do another 50 after that then the last 50 will take care of itself. Flawed reasoning but we had a feeling it could be done.

The lockdowns ended and the idea was forgotten. Cycling was always one interest competing with a hundred others and it once again fell by the wayside with the exception of a three day bike packing trip to Newcastle in 2022.

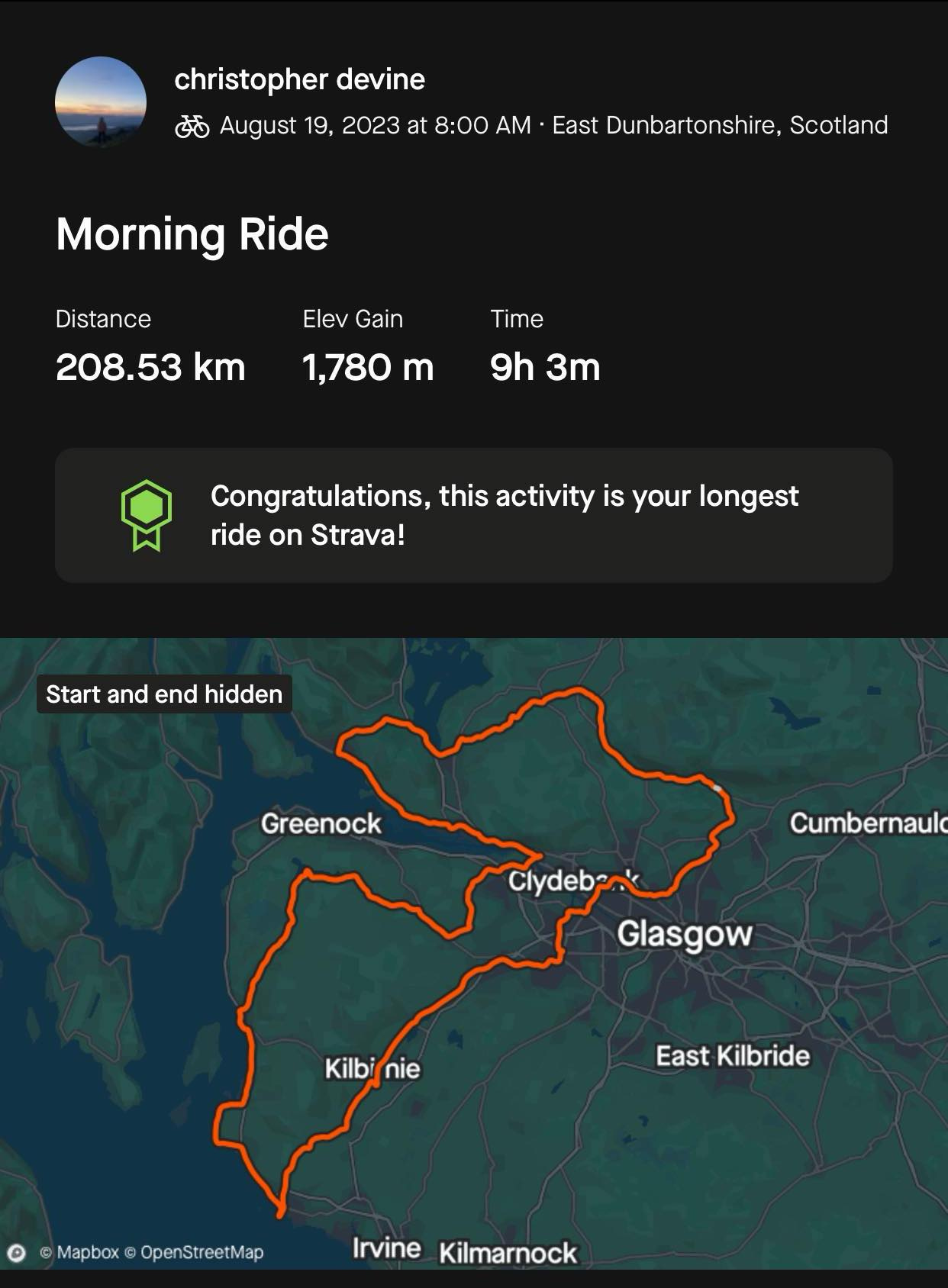

I can’t remember how but the idea resurfaced in 2023. My friend Gregor and I were going to do it. We were going to go further on a bike than we or anyone we knew had ever gone.

We knew we weren’t pros, we had no formal training or knowledge of how these things worked. That was part of the appeal, we were going to cross the country completely off our own merit.

It was the same premise as that 31 mile cycle to Edinburgh, and the same feeling of adventure and the unknown. In one go, we would leave the Central Belt and head due north to the capital of the Highlands and not sleep till we got there.

Good friend and colleague Fin was roped in for the effort and on an April morning at 9am we set off from my flat on Great Western Road. Destination: Inverness Train Station. Distance: 206 miles.

It was a momentous journey. Unlike anything we’d attempted before. The details of which are a story in their own right. High points including stopping at Prince of India in Pitlochry for a late night curry before tackling the night shift over the Drumochter Pass; the highest point on the National Cycle Network.

The low point was at Aviemore. Temperatures dropped below zero. Low on energy and sleep deprived, we got real cold. Fin bonked.

We asked if he wanted to jump on the train at Carrbridge and call it quits. He persevered.

At 11am on Sunday morning, 26 hours after we’d set off, we rolled into Inverness victorious.

Experiencing the gradual changes of landscape, the movement of day into night and slowly back into day again put me in touch with nature and the world more intimately than perhaps anything I’d ever done.

The feeling as the sun sets, knowing you must embrace the darkness in a terrain unfamiliar to you is terrifyingly exciting. Nowhere to sleep or rest, only you and the bike.

The optimism as you see the first specs of light after the darkest hour is unmatched. In everyday life, you take the return of the sun each day for granted. Cycling through the night, which shrinks your world down to a small illuminated ellipse created by your bike light, helps you appreciate this simple miracle.

It was around this time that I stumbled upon the world of Audax.

Part II: Audax

Randonneuring is long-distance unsupported endurance cycling. This style of riding is non-competitive in nature, and self-sufficiency is paramount.

It turns out one of the oldest cycling sports in the world is basically what we had been doing. Known interchangeably in the UK as Audax or Randonneuring. Participants ride ultra-distances without any support crew within a set time limit, including stops to eat or rest. There are no times or medals for first place, to win is to finish.

Before an Audax ride, you’re given a brevet card. The card signifies points known as controls along the route that you must gather proof you were there in order to finish. Some controls simply state a town name you must collect a receipt from. Others have volunteers waiting to stamp your card. Others simply ask a question you could only know from having been there (How many whiskies does the hotel at John o’ Groats sell?).

I looked further and found there were events all across the country all year round of various distances. This was great, routes decided for me with like-minded people. I had to get involved and see what it was all about.

Gregor and I completed our first Audax alongside roughly 30 other riders in August last year. 200km.

From here, we learned there’s a title in the world of Audax that all riders aspire to.

The Super Randonneur.

To earn this title, you must ride a 200km, 300km, 400km and 600km Audax. All in one season.

If completing this is what’s considered respectable in the world of long-distance cycling, I had to give it a go and see how I stacked up.

Furthermore, we discovered if you complete each distance in a different country you’re awarded the prestigious title of International Super Randonneur. This was a chance to truly see what’s over the horizon and cycle places I’d never been before.

I loved the idea of it, our sights were set on 2024.

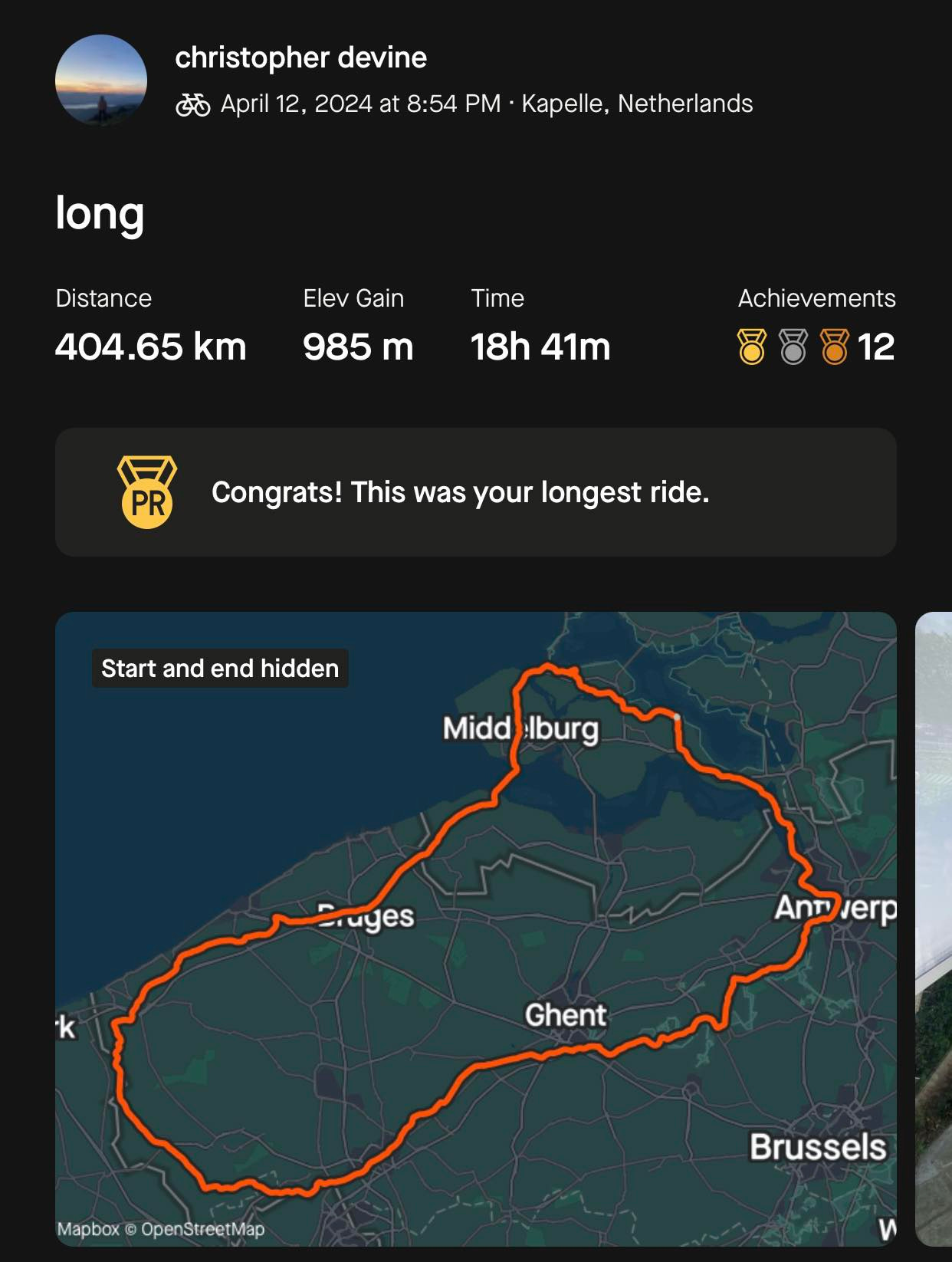

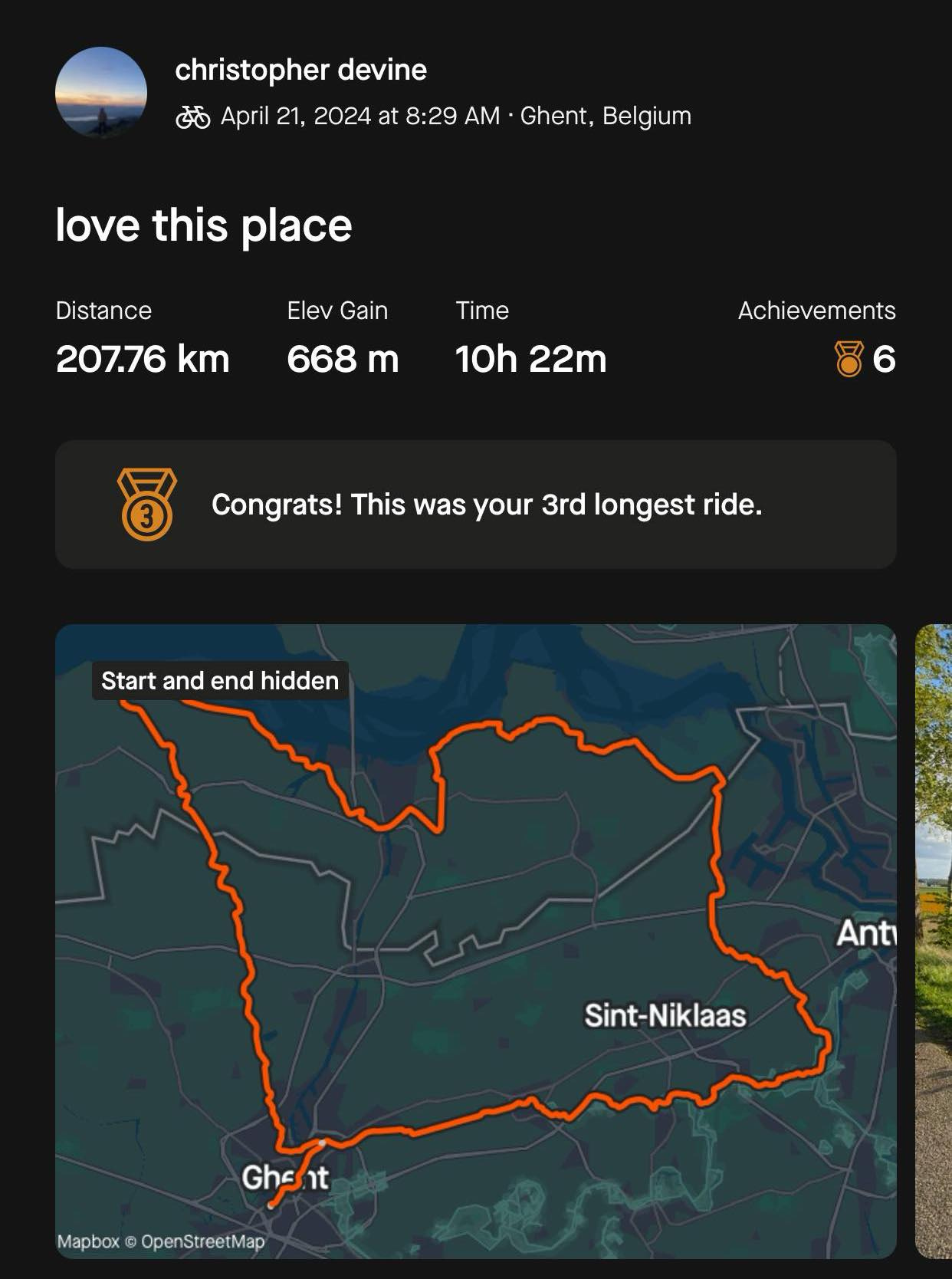

After much research and deliberation over the winter months, we had our first targets. A 400km in the Netherlands in April and a 200km in Belgium a week later. Sticking to the Low Countries worked in our favour with limited time off work and reduced travelling costs.

We knew we wanted to do the 600km on home turf. There was one in the far north of Scotland in June that sounded amazing. The nights would be lighter and if we failed, we would still have plenty of time left in the year to try again elsewhere.

It turned out there was also a 300km in France the day before our 200km in Belgium, if we could somehow do that and travel straight to the start point of the next, we could knock out three distances in three countries over two weekends. We decided we’d make a call after the 400 if we were feeling up to it.

The 400 was tough. Things were going well and I was feeling strong. Then I started to get tired.

The event had begun at 9pm, so we’d already lost a day and felt like we were winding down for the night when we had to set off. The sleep deprivation started to hit hard around 5am. I bought a Red Bull from a service station, emptied it into my water bottle and carried on.

There were high and low points in our energy. Morale always remained high, but the urge to sleep was overwhelming. I wasn’t completely hallucinating but I was mistaking sign posts for people and stones on the ground for animals. My depth perception was all over the place.

About 300km in we decided to stop for five minutes and just rest before the final push. I tried to close my eyes and steal a five minute power nap but by this point I was three or four Red Bulls deep and my exhaustion was matched only by how insanely caffeinated and on edge I felt. No sleep for now.

It had never grown louder than a whisper in my mind, but for the first time on a big ride there were moments where I had doubts I would be able to finish. I got into a bad habit of staring at my Garmin screen, feverishly watching the distance tracker as if that would make it tick by faster.

Slowly but surely though the miles passed us by and as we drew closer to the finish, paradoxically our energy levels rose. We were going to do it.

Accompanied by a beautiful sunset, we arrived back in the Dutch town of Wemeldinge, 400k and 23 hours later.

Upon finishing, I received a handshake and a “how was it?” from the organiser, and that was it. No pomp or fanfare at the end of an Audax. I like that. It seems all too easy to give yourself high-minded ideals for doing something when really you’re just chasing attention. Audax helps me feel I’m not telling myself that lie.

We spent the next six days staying across the Low Countries with various people, an adventure in itself. Honourable mentions include:

Staying with politician turned teacher Gerard and his wife. Both now retired, they let us stay with them alongside a Ukrainian refugee. Two of the most interesting people I’ve met, during dinner Gerard received an urgent call from the local government asking his advice on an outbreak of disease within the Dutch lobster population. The next day he was on a panel judging an art competition in the nearby town. I’m grateful for their generosity and hospitality.

Eefja, who let us crash on their couch, cooked us pasta and took us to the pub in Middelburg.

Part time actor Dirk, who let us stay in his living room. An interesting fellow who stayed up all night with Belgian techno blasting from his radio next to where we were lying while he simultaneously watched French slasher movies across the room until the early hours of the morning. He eventually fell asleep in his bed with the door open which looked onto where we were trying to sleep. Not to mention the large print of himself dressed as a medieval peasant from one of his roles looming over us. We left a bottle of whisky on the table with a thank you note, quietly packed our things and made a beeline for the first train to Brugge.

Isabelle and her family who we stayed with in Béthune, France. Chatting late into the night by the fireplace about French history, French-Anglo relations and how much bigger the cheese aisle is in a French Lidl, not to mention the amazing food they cooked us. It made me feel welcome for my first time in the country and for that I’m grateful.

I was hoping this interim would let me recover in time to give the 300 in France a go and then the 200 in Belgium the day after. But it seemed like the 400 paired with the added pressure of work (I was working digitally during this time to save annual leave) had taken it out of me. I decided to commit to the 200 in Belgium and leave the 300. Gregor was faring much better and decided to go for it.

We parted ways in Béthune and agreed to rendezvous at the accommodation we had sorted for the following night before an early rise and train to the 200 starting point in Ghent.

No complaints on this ride. The sun was out for most of the day and the lack of wind and elevation made for relaxing cycling. Gregor fared no worse despite having finished the 300 less than 24 hours previously.

The weeks following our return saw me struck down with illness and a general foot off the gas. I felt like we’d accomplished something and I wanted to focus on other things for a while.

It was only at the start of June when Gregor sent me a screenshot of his confirmation email for the 600 that I fully realised how little time there was to prepare.

I flip flopped for another week, wondering if I had enough time to prep. If I could get the time off work. If I was ready for such a huge undertaking so soon.

If I didn’t do it, I’d have to find another 600 in England later in the year.

No, it had to be this one, it was the toughest 600km Audax in the UK and it was on home turf. If I wanted to do it, I had to go all in.

With three and a half weeks to go, I pulled the trigger and applied.

Part III: The 600

“Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.”

- T. S. Eliot

The next three weeks saw me average 200km per week in training rides, with the last 5 days set aside to rest, sort my gear and pack.

It was a stressful period. I knew I was fit but I didn’t feel strong enough. I needed a foundation of big, low intensity miles. Big miles take time. Work, weather, life were constantly getting in the way.

That isn’t to say I had it harder than anyone else who’s ever had to train for something similar. The simple fact is it requires a lot of your time and energy and it was hard to sufficiently prepare without neglecting all other areas of my life.

I found myself saying no to more and more things I would otherwise liked to have had done to make way for training. Easily distracted in conversations thinking about logistics and gear, it consumed more of my life than I realised it would. Questions on fueling, training schedule, diet and a million other things constantly revolved around my head.

The more time and energy I invested, the bigger the price I was paying in all other areas of my life. The bigger the price I paid, the more I wanted what I was paying for.

This was my state of mind as the date drew closer, while simultaneously feeling I hadn’t done enough. I put my odds at 60%.

The scheduled start was 6am on Saturday June 29th at North Kessock Village Hall, just outside of Inverness, with the option to stay in the hall the night before.

We got the 15:07 train from Glasgow to Inverness on the Friday and with that the die was cast. No turning back now. No last minute changes to gear, what we had with us would have to do.

Upon arrival we were handed our brevet cards and left to eke out a space on the floor for our sleeping bags. The atmosphere in the room felt somewhere between somber and tense, or maybe I’m projecting my own feelings. We shared a whisky and a couple exchanges with a few other riders but I was distracted. Despite there being nothing more I could do, it felt wrong to not be preparing in some way with such a huge undertaking less than 10 hours away. But all the bike bags were packed the way I wanted, my clothes were laid out and ready, everything was charged, my bike was clean and working well. The best I could do now was to relax and try get some sleep.

Four or five intermittent naps later, I was stirred by a sudden increase in activity outside the protection of my sleeping bag. It was 5am, porridge was being served and all around me, riders were zipping up jerseys, rolling up their roll mats and lamely walking to the far side of the hall to grab a bowl.

With it being a week out from the Solstice, it was broad daylight outside at 5am. It felt surreal to be thrust into a breakfast in what felt like the middle of the day with 30 strangers after half a sleep. However, nervousness had been replaced with excitement. No more waiting, preparing or training. For the next 40 hours I just had to ride.

The route was set to loosely follow the famous North Coast 500 trail around the Scottish Highlands with a total elevation of 6,200m. For comparison, Mount Kilimanjaro stands at 5895m. It was going to be the equivalent of cycling the height of Ben Nevis four times over.

The deadline was 10pm on Sunday evening, 40 hours away. This meant you had to average 9.3mph including all stops to make the cut off. If you’re able to cycle faster then you can buy yourself some time to grab some sleep, so whenever you stop to stretch your legs or refill your water, you know in the back of your mind your wasting valuable sleeping time.

Three of the controls had options for a small bag drop. This meant you could pre-pack a bag with something to sleep in and send it ahead. Gregor and I opted for the control at Watten Village Hall, 372km in. If we matched our 400k pace then we would arrive in Watten at 1am, time for 4-5 hours sleep if we wanted it. However, the elevation on this route made us painfully aware we weren’t going to be that fast. Whatever time we arrived at Watten, we would need to leave by 7am latest to ensure we made it to the end on time. We had no idea when we could expect to arrive.

On top of this, the weather wasn’t looking great. Rain could be expected for most of the Saturday with a strong westerly wind. Temperatures weren’t set to exceed 12° with lows of 8° during the night. My weather app informed me the wind would ensure it felt closer to 4°.

5:55am - 5 minutes till we start. I notice 22 unclaimed brevet cards on the table, it seems a lot of people thought better than to go through with it. An ominous sign.

I wheel my bike out the village hall alongside everyone else into the fresh morning air. It’s cold and clear with pink hues streaked across the skies, menacing clouds to the west, where we’re heading.

Andrew the organiser offers us good luck, counts down from three, then to the sound of dozens of Garmins being turned on, we’re away.

About 20 extra riders joined in the morning bringing our total to around 50. We’re all bunched up and mostly silent as we roll out of North Kessock. I noticed this on the 400 as well, it seems it takes a few miles before everyone loosens up. The ice is broken when two American bike tourists on the wrong side of the road cause all 50 of us to swerve at the last minute. Clearly oblivious to their infraction, it gets a few laughs.

As the landscape opens up and the headwind becomes more pronounced, I try to take shelter among the largest group of riders. The pace is slightly faster than I’d like but I figure it’s better than battling the headwind solo all the way to Ullapool.

I glance behind me and notice Gregor is nowhere to be seen. Either he’s in the group of riders half a mile back or he’s stopped for a pee and will catch up. It happens often and I assume I’ll see him shortly.

The countryside starts to feel remote real quick. A light rain moves in that feels worse due to the wind. For now though I’m warm and happy, the rain should finish by late afternoon and that’ll be the worst of the weather out the way. Cycling alongside a desolate reservoir, a car tries to overtake us at high speed into an oncoming car with it’s car horn blaring. It swerves and threads the needle between us and the other car with barely two feet either side to spare. Not a great omen considering the notorious reputation for some drivers on the NC500 I’d been made aware of.

The group I’m riding with have all cycled this distance before, I’m the newbie of this pack. I manage to stick with them as far as Ullapool but I tell myself I’ll need to go it alone afterwards to avoid exhausting myself too early.

Ullapool is the first control and it requires a receipt. I find myself in the Tesco foyer with about 8 other riders all eating various meal deals. The rain hasn’t stopped and as soon as I find myself not cycling the cold sinks in fast. Looking around though, everyone is damp and feeling the chill. We’re all reluctant to leave the safety of the Tesco foyer.

What worries me is how much worse it’ll be in 10 hours when I’m tired. I decide not to think about that.

After sending a message to Gregor to let him know my whereabouts, I ventured back out into the biting wind and monotonous rain. Thankfully there’s a big climb straight out of Ullapool that gets me warm fairly fast. 85k done.

On my own now, I wasn’t sure which way my mood would go. Not focusing on staying with a group let me appreciate the scenery and relax. The nervousness left me, I was able to get into a rhythm and just enjoy cycling through the dramatic landscape. I was also now heading due north which meant the headwind had eased into more of a crosswind.

I barely saw anyone for the next 70km, including cars. It was peaceful. Having the road to myself in such a remote area of the country was a joy. Upon realising how good I felt, I made a mental note to myself to channel this optimism later when the bad times inevitably came.

Some serious climbs tried in vain to dampen my mood, the views at the top were always worth it.

The rain came and went so consistently it was almost soothing. I knew it would always end. Not having the headwind helped massively.

Next control was in the tiny village of Scourie. I spotted a few riders inside a small cafe and went in to join them. The warm pastries they served worked wonders.

153km done. A significant distance in it’s own right, it’s easy for the exhaustion to hit hard as soon as you’re sitting in a warm cafe. From inside, the rain outside looked utterly disgusting. Maybe I’ll stay here five more minutes and see if I can contact Gregor.

A few riders were huddled around the coffee machine in the far corner. I toyed with the idea of a coffee but resisted. My plan was to save any caffeine until deemed absolutely necessary lest I get in a runaway loop of more and more coffee and find myself unable to sleep at Watten, similar to what happened in the Netherlands.

Gregor texts me saying he’s climbing the hills outside Scourie, this is good news considering I hadn’t heard from him since just outside North Kessock. I wait ten more minutes then decide to head on and hopefully see him behind me soon.

If I thought the last section was remote, the next 40km was totally desolate. I wasn’t seeing much of anything man-made let alone other riders or cars. There was a Jurassic quality to the terrain that came from the untouched and bleak aspect of it’s nature, ferns and bare rock punctuated the hillsides. The rain remained consistent, everything was shrouded in mist and damp.

The fatigue that had set in during my cafe stop evaporated and let me enjoy where I was. After cresting a particularly long ascent, I was greeted with an all-encompassing panorama: a wide green valley flanked with huge hills on either side. It wasn’t an especially dramatic view similar to what I’d been seeing but it blew me away with it’s utter proportions. It was a huge expanse before me, completely untouched except for a winding descent snaking as far as I could see. I think it was the lack of anything in the foreground. I could see so far.

Flying down into the valley at high speed, the clouds broke and I saw blue skies and felt the sun on my face for the first time today, it served to enhance the views before me to euphoric proportions.

Durness was the next control at 194km. While taking refuge in a bus shelter with a chocolate spread sandwich, I spotted Gregor rolling into the village. We exchange notes; we’re feeling good. Worked but good. Better yet, the weather was clearing.

Onward then. Next control was Tongue, 60km away.

We left in a loose group with one or two other riders, but quickly all separated again as we rounded Loch Eriboll. The undulating hills and use of passing places didn’t work well for sticking together it seemed.

I was alone as I climbed the hill on the far side of the loch. It offered huge views out to sea. What really magnified the beauty was the lack of anything built into the landscape. Loch Eriboll was used in times past as shelter for ships caught out in storms on the north coast, with how tranquil it looked, I could see why.

The route kept climbing higher as it left the loch. What followed was views over a massive expanse dominated by the most northerly Munro: Ben Hope. It stood solitary, nothing else to distract your eye, it’s rugged edges in sharp contrast to the grass and peat that surrounded me.

The subsequent long descent down off the plateau into Tongue was a highlight. Cruising at 45mph with nothing but an incredible landscape before me. It’s these special moments that make it worth it.

The control at Tongue was a small village hall filled with half a dozen riders and some volunteers who had prepared food for our arrival. I got my brevet card stamped and took 4 slices of toast and a cup of tea with about 8 sugars. Gregor arrived about ten minutes behind me.

242km done. 358 to go.

It was getting late now, we’d been cycling for about 14 hours and our thoughts turned towards our chances of sleep at Watten. It was 40 miles to the next control at Thurso and then a further 30 to Watten and the promise of rest. Gregor uncomfortably pointed out that’s still a whole day’s cycling away. A rider sitting next to us at this point decided to call it quits then and there. I hoped there wasn’t something he knew that we didn’t.

Gregor, I and three other riders left Tongue at about the same time but again, I found myself alone a few miles later. The darkness was starting to close in and with it, rain.

I stopped briefly and gave Gregor a call to see if he was close, no reception.

A solitary rider caught up with me while I was stopped and we ended up riding together for the next couple of miles, we never exchanged names but he was from Hertfordshire. We chatted for a bit and then slowly drifted apart as the rain got heavier and daylight faded.

The mist had returned and I couldn’t see much except the road in front of me. Everything was silent except the sound of my wheels against the asphalt. Suddenly the sun soaked views of earlier in the afternoon felt a long way away.

Each mile started to pass just as the last had with little change. The mist made everything look the same. It was a liminal, horror-esque environment, but I liked it. Apart from a lone deer, I had nothing but my thoughts to keep me company.

I caught up with two riders not far from Thurso and stuck with them for the last few miles, I was getting tired now and the rain and darkness hadn’t helped. The thought of almost being at the control had kept my spirits high.

Thinking I was minutes away, it crushed me when I saw the sign:

John o’ Groats 20 miles.

In a moment of exhaustion induced idiocy, I’d got Thurso and John o’ Groats mixed up. I thought I was close but instead I was still two hours away from the control and then it was about 30 miles after that to Watten. The thought of being about five hours from any chance of rest devastated me, I think I’d started to mentally switch off thinking I was closer than I was.

It’s a weird thing, although a mile is always a mile, how it feels can vary drastically depending on your mental state and the conditions you’re facing. The prospect of 50 more miles suddenly felt horrifying.

The rain had grown more intense and it was completely dark now. My energy dipped and the two riders I was with slowly disappeared, their red rear lights getting smaller and smaller until they vanished into the darkness, mist and rain.

I had some very close passes from cars leaving Thurso, I wondered if they were taxis taking people home now that the pubs were closed. I guessed it was about midnight. Visibility was terrible, my front light illuminated the rain in front of me which made it almost impossible to see more than a few meters ahead. It started to get really cold and despite having two flashing rear lights, I didn’t feel safe with the cars. I don’t think they were expecting to see someone on their bike in the near middle of nowhere in the middle of the night in the pouring rain and wind.

The only real option at this point was to continue, I was dangerously exposed and if I stopped for more than a minute I would get terribly cold. Without phone reception or shelter this wouldn’t be a great spot to give up or get stuck. Exhaustion was starting to creep in and my toes were going numb, the wind-chill must’ve put the temperature not far above zero.

If there was a way to have given up at this point I can’t say for sure that I wouldn’t have taken it. The position I was in however, forced me to continue and I guess that’s good in a way, although it didn’t feel it at the time.

I can’t remember too well what was running through my mind at this point, I think I was just trying really hard not to notice that I was on my own for miles around with nothing but driving rain, freezing wind and darkness for company.

The state I was in led me to conclude that Gregor must’ve bailed at Thurso, surely he’s smarter than to carry on. That might not sound obvious but tiredness in such conditions has a way of making you think things and not dwelling on it’s validity, you just form opinions and decide it’s fact. At least that’s what happened to me. I was truly on my own now.

It was then as I was passing through a small village that I noticed a bike propped up against a wall, this caught my eye long enough to spot a cyclist standing in the doorway. I slowed down wondering if it was an audax rider, maybe they need help. After wheeling round and approaching the door, I could see inside and what I saw felt like a mirage in the desert.

This was the control in the village of Dunnet. Yet again in my tiredness I’d made another almost critical mistake. I’d had it in my head that the next control was John o’ Groats. I should have probably paid more attention to my brevet card, I hadn’t really looked at it since breakfast that morning. What an idiot! If I hadn’t seen that rider outside I would have cycled right past and been disqualified. Any feeling of annoyance I might’ve had was overshadowed completely by the total relief I felt to be somewhere warm and dry, as I walked in I was offered a hot bowl of soup and a cup of tea. After thinking I had another three hours of slog ahead of me before any respite, it felt almost too good to be true.

Sitting at a table grasping the tea with both hands, I heard from other riders how they’d fared, seemed like it was tough going for everyone. I decided to stick with two other riders for the next leg, being out on your own in that rain wasn’t fun.

This moment of comfort was a miracle cure for me, the soup and tea warmed my body and spirit. I was ready to face the last 30 miles to Watten.

The short distance to John o’ Groats was fine enough, we chatted and kept ourselves distracted from the conditions. They told me stories of rides they’d done in freezing snow and ice with riders having to quit due to hypothermia, it made me feel a bit better about our situation.

The John o’ Groats control was the previously mentioned question How many whiskies does the hotel sell? Turns out 100 is the answer.

At this point the route turned straight into the headwind, I found myself struggling to keep pace with the other two and I was forced to focus on the rear wheel of whoever was in front and just dig in.

The miles kept ticking by and I found myself scared to check the distance, simply praying we were close to Watten now. My memory of this part of the ride is simply darkness and rain, broken only by the red rear light in front of me, drawing me along like a moth but never getting closer, like when you run in a dream.

It truly felt like it would never end, that maybe I was destined to be in the dark, cold and wet forever. Then, out of the darkness a sign lit up, reflected by our bike lights.

Watten 1 mile.

I was overjoyed, albeit numbed from the cold and tiredness.

We rolled up to the village hall, parked our bikes round the back under the still incessant rain and made our way inside. 372km done. The time was around 2:45am.

Strewn across the village hall were riders in sleeping bags, some just on roll mats in a fetal position. One man was lying on two opposing chairs in a horribly contorted position, I have no idea how that was comfortable.

I got my brevet card stamped and was offered a hot bowl of pasta, I’ve ate few things as satisfying as that macaroni cheese.

My drop bag was in a pile of other bags in the corner, I got out my roll mat and sleeping bag and set up under one of the tables. All my wet clothes were laid out on the table above me. Not the best place I’ve ever found myself having to sleep, especially considering the entire hall was brightly lit to accommodate for riders coming in through the night, but it felt luxurious. I cocooned myself in the sleeping bag around 3:30am and found myself drifting off fairly effortlessly, understandable given the circumstances.

I was thrust back into reality about 2 hours later. There was a general commotion around me as people packed up their things and got ready to continue on. Upon reluctantly poking my head out the sleeping bag, I locked eyes with another rider, we didn’t say anything but the looks on our faces communicated enough.

I didn’t feel too bad in the grand scheme of things, of course if I had felt the way I did in any other context I would have described it as far from okay. Getting this far meant the end was in sight though, maybe I’d actually pull this off. So all things considered I was in a good mood.

I was about to go and ask a volunteer if Gregor had arrived last night when I suddenly saw him lying in the far corner facing the wall. He stirred as I walked over, a silent thumbs up from both of us was enough to know we were winning.

Most riders were out the door by 6am, I peaked outside and my heart dropped, grey drizzle and a generally dreich atmosphere. We decided to take our time leaving and try to warm our socks on the radiator before facing it.

Half an hour later we were reluctantly back outside and on our bikes, we immediately both exclaimed that our knees were aching bad. I think the two hours of rest tricked my body into thinking we were done and now I was really feeling the toll of the last 372km.

The route took us straight into a headwind and progress was not fast. All in all, it was fairly miserable conditions what with the weather and the state of our bodies.

Regardless, we found ourselves joking and making light of the situation, it was comical that we had decided to do this in the name of fun. We couldn’t deny though, that this was a real adventure.

The going was incredibly tough, we passed another rider in a bus shelter who looked completely done. We asked if he was okay or needed help, he said he was fine and waved us on.

Finally the route turned south into a valley that sheltered us from the wind, almost immediately our energy levels rose. When you’re exhausted I’ve found your emotions become much more a slave to your environment as if you lack the energy to have any say over them. Extreme highs and lows happen at the whim of your situation, almost toddler-like. Instead of despairingly joking at our state as a sort of defense mechanism against adversity, we were now having a laugh because things were good.

The next control was a remote church in the village of Strath Halladale. Sunday service was starting just as we arrived so we hurriedly got our brevet cards stamped, accepted three cheese sandwiches from the nicest people ever and got back on the road.

Knowing there was only 185km to go felt good. Once we were under 100km we told ourselves, we were safe, no matter how destroyed we felt we could always grind out a last 100km surely. I tried to quash the sudden nightmare of my bike falling apart 20 miles from the end causing me to DNF.

The rain had eased and things were looking good. I have no memory of what we chatted about but we were having fun. Careening down a narrow section of path, Gregor clipped my rear tire and swerved, almost going head first through a cottage window. Maybe it wasn’t as dramatic as it felt but tiredness has a way of accentuating these things.

We were then rudely thrown back into the headwind as the road entered a vast valley. If I lack detail here it’s purely because I can only recount it as a blur, the broad brush strokes. Having to dig in and mentally detach yourself from miles of slow, uphill slog doesn’t lend itself well to recounting it later.

Gregor had a panic that at this rate we wouldn’t make the cut off at 10pm. I reasoned that this was the slowest we were going to be, once we turned south at Altnaharra it would be mostly downhill and there would be no more headwind. I felt, or maybe just hoped that we would make back our time in the second half of the day.

During this time, my knees were getting more and more inflamed and I prayed they would last the rest of the day. They felt swollen from overuse, not from bad posture. I told myself that meant it was fine to push it without too much risk of injury. Add it to the list of split second opinions formed and not questioned during a sleep-deprived cycle.

As we reached Altnaharra, the clouds finally broke for the final time and made way for what started to turn into a lovely day. I was able to take my damp gloves off for the first time.

Next control was The Crask Inn, an oasis in the wilderness. A truly remote spot. After this point though we knew we were in the home stretch, I figured we were due to arrive at the finish about 45 minutes before the cut off which felt a bit tight. If anything went wrong, we might not make it. Regardless, knowing we had only 93k left to go paired with what had turned into a beautiful afternoon was enough to keep us chipper. After demolishing a toastie and emptying about ten tablespoons worth of sugar in my water bottle, we continued on.

What followed was mile after mile of constant downhill, the warm breeze and sun against my face almost made up for the hours of darkness and rain that were already beginning to feel like a fever dream.

As well as things were, I knew I was sitting on a time bomb. To protect my inflamed knees, I can only assume I had subconsciously adjusted my posture on the bike because now my Achilles was becoming overwhelmingly painful. I took two paracetamol with caffeine and hoped I could stem the tide until I was done.

As we drew closer to the end, the pain in my knees and Achilles grew exponentially worse, reaching a climax not far from the final control at Dingwall. Before me was the second largest climb of the entire route and by this point I was barely able to put pressure down on my left leg. I found myself relying almost entirely on my right leg to power me up the hill. For what it’s worth, the pain kept my sleep deprivation at bay.

Cycling towards Dingwall, I started to forget I was on a bike. I’d been in the same fixed position for so long I’d grown fully accustomed to it and I kept snapping to, remembering I need to hold on to the handlebars. It’s hard to explain how it felt. I remember thinking how comfy it would be if I fell off my bike now and ended up in a grassy verge. I also found myself being jump-scared by my own thoughts as I came to after moments of total detachment from the situation I was in.

The control at Dingwall required a receipt, we jumped into Lidl and bought the first things we saw. We were eager to finish now.

It was turning into a pleasant evening, the sun had set without me noticing and it felt like the curtain was closing on the ride. When I realised we only had ten miles to go, all my suffering dissipated.

The final stretch across the Black Isle into North Kessock felt almost like the victory parade, the dawning realisation that we were actually going to do it was an intense and complex feeling. Overwhelming joy mixed with an irrational sadness, almost like a sort of Stockholm Syndrome for the ride itself. It was coming to an end and I wasn’t sure what to make of it. Outwardly, I couldn’t stop smiling. I remember those last ten miles as one of the most fulfilling moments I’ve ever experienced.

The victory song my Garmin played as I reached the finish was almost too much to bear. 40 minutes before the cut off. We’d done it.

Part IV: Done

We stayed in the village hall again that night, up at 4am for the first train back to Glasgow. 12 hours after finishing I was sitting back in front of my desk at work on Monday morning.

Of the 72 people who entered, 22 didn’t start and 10 didn’t finish. I heard from experienced riders that it was a tough event, even by their standards. It took me a good few days before I could walk normally again.

Having dedicated so much mental and physical energy into doing this throughout the year, it was weird that it was now over. I don’t know what I was expecting but it was strange that upon finishing I was instantaneously thrown back into a normal routine, with evenings spare and a chance to let my mind idle for a second. Usually I can’t stand not feeling like I’m working towards something but for now my thoughts are quiet, I want to make the most of that and be present for a period.

People sometimes ask how I find these sorts of cycles fun, but it’s about so much more than that. The experience is much deeper and richer than a superficially fun activity. The lows are lower and the highs are higher, it’s like life with the intensity dialed up.

Additionally, while you’re on the bike on these long rides, you’re not worrying about anything else, it is all consuming. It slows down and simplifies what is usually a complex and hectic modern lifestyle, you just have to pedal and watch the landscape pass you by, for that brief moment it’s your entire reason for being, which is a nice respite for a busy mind.

What’s more, it makes you intensely more grateful for simple luxuries in life, you’re stripped down to your base needs, to be warm, dry, fed, well-slept. Everything becomes simple. Modern living is stripped away until only what matters remains.

You’re connected to nature with no source of instant gratification at hand. In taking on a huge feat you’re submitting to something greater than yourself and the only way through it is to endure. Through enduring you learn more about yourself and in overcoming it, you develop a resilience and confidence that permeates into every aspect of your life.

Modern life is full of things such as drinking, fast food and social media that provide a momentary spike in happiness but which erodes your baseline level of happiness over time. These long rides have acted as an antidote to this, strengthening my character, putting me in touch with nature, making me more grateful and giving my mind some peace and quiet, just for a few hours.

Thanks to Erin, Gregor, Fin, Luc and everyone else I’ve shared a cycle adventure with.

Thanks to Andrew for organising an amazing 600km experience. If you’re interested in riding a similar audax up north, you can find more here:

https://audaxhighland.wordpress.com/

Thanks to Liisa for capturing it all. https://www.instagram.com/off_course_photography/

And to anyone else who put up with me and gave me the time of day when all I had time for was training or prepping.

Hi Chris, we chatted a little in Scourie. Thanks for a great account of the ride and your own experience. Very much enjoyed.

Loved reading this Chris!! So inspiring !!